For an upcoming novel, the narrative demanded that a character be flung off of an asteroid, and spend about 30 minutes falling back to the surface, because of the lower gravity involved. As originally written, the chapter is set on the asteroid Ceres. However, a little voice in the back of my head said, “Maybe you should check to see how fast things fall on Ceres.” The trouble with little voices in my head is that they just don’t shut up until heeded. And yes, gravity is high enough on Ceres that it doesn’t take anywhere near 30 minutes for someone to fall from 300 meters. It’s more like less than a minute. And that just wouldn’t do.

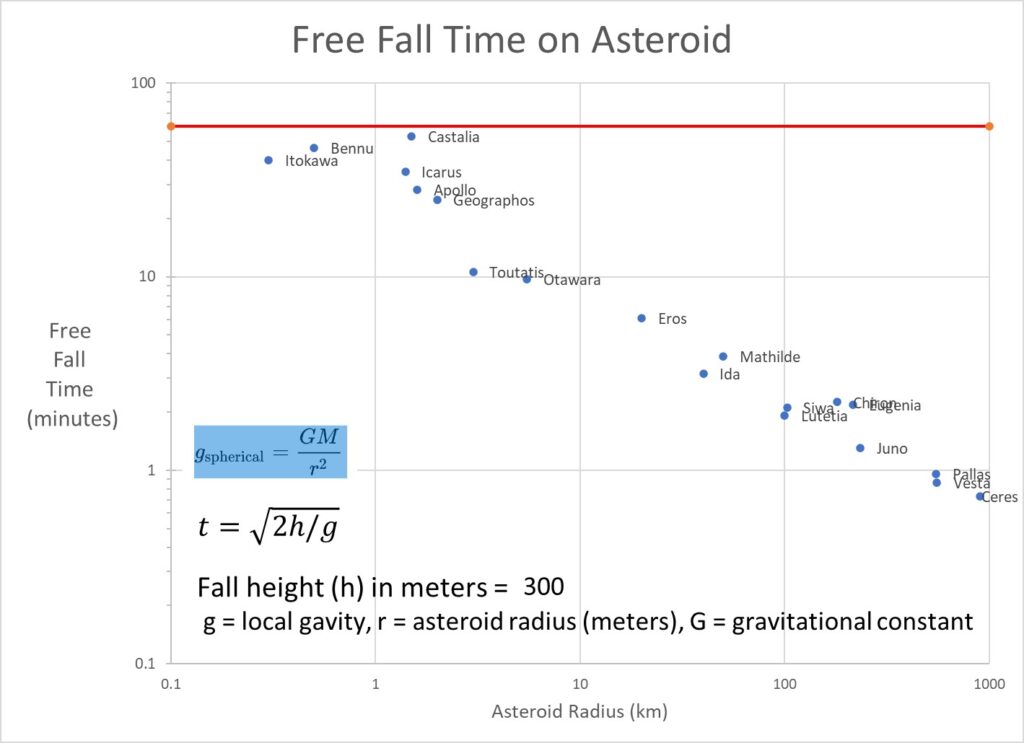

So, I had to go shopping for another asteroid to set the action on. In the course of that odyssey, I constructed the graph which ought to accompany this post, if I’ve done it right. I’m not writing this to brag on being good at math. Because, frankly, I’m not. I’m okay at math, and remember just enough algebra from engineering school to figure out how to use the equations websites say I’m supposed to. My career taught me how to use Excel, which is where the graph came from. Quibbles from people who point out that I didn’t take the mass of the falling person or general relativity into account are most likely entirely correct. I really don’t know what I’m doing. I just pretend like I do. Which, oddly enough, usually works.

The whole point of this post is to demonstrate that you don’t have to know what you’re doing these days. At least not when you start out. People falling to asteroids was a mystery when I embarked on this task. Quickly enough though, I had picked up just enough knowledge to be truly dangerous. That knowledge came from the internet.

I have stumbled upon a powerful secret. If you simply go to a search engine (Google, Bing, Yahoo, etc…) and type in a question, you will probably be presented with a number of answers. “freefall time on an asteroid” yielded, among other results,

https://forum.cosmoquest.org/forum/science-and-space/space-astronomy-questions-and-answers/59313-

and, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Free-fall_time

Some of these sites were more help than others. But I was able to cobble together enough of an understanding from them to answer my question: Ceres is too darn big. Gotta move to a smaller rock. Wikipedia then coughed up a comprehensive list of asteroids in our neighborhood, complete with sizes and masses. The end result was the graph, and I followed the data points up and to the left until I found a suitable asteroid above which my character would drift for about 30 minutes.

None of this was really necessary. I could have instead employed the ingenious literary technique of simply not mentioning the name of the asteroid in the story. That would’ve worked just as well, because nobody knows what the gravity is on my imaginary rock. But details like actual place names add to a story.

The internet has greatly simplified this type of research. In the early 2000s I was writing a story in which a riot erupts near the White House. Google Earth was new, so I could get ariel views, and that helped. But I don’t think the street view option was up and running yet. I needed details like sightlines, pedestrian patterns, and how other protests unfolded. They get a lot of protests around there, it turns out. My solution was to place a long-distance call to a hotel fronting on the fictional riot site, explain to the desk clerk who I was (and still am), and why I was asking these strange questions. It must’ve been a slow evening, because the clerk talked to me for something like 15 minutes. If that didn’t get my name on some FBI shady characters list, nothing will.

These days, type in an address anywhere in the world and you most likely will get a street view out front, and maybe inside. Click on a restaurant across the way, and a bar graph of how busy it is throughout any given day is available if you just scroll down the page. Compared to how it used to be, that’s nothing short of amazing.

This isn’t limited to Earth, or even our solar system. A list of potentially habitable planets under other stars is a few keystrokes away: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_potentially_habitable_exoplanets. Need to describe the night sky on a planet in a distant solar system? https://skyandtelescope.org/astronomy-blogs/explore-night-bob-king/see-the-sun-from-other-stars/. How about examples of alien biospheres? https://tch-forum.com/showthread.php?tid=3966, or https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2022/09/search-for-extraterrestrial-life-aliens/671410/. How about the physiology of dragons? http://draconian.com/body/body.htm.

The point is that there’s so much information to help you build worlds and describe settings at your fingertips these days. We used to have to trudge down to the library to access even a fraction of what’s right there on your laptop or phone screen now. Of course, you still have to drag the story out of your head and stitch it to the page, one keystroke at a time. Can’t help you with that part.